“It’s useful to remember that writing is not natural because writers tend to judge their writing processes too harshly—comparing them to the ease with which they usually speak. Speech, however, employs an extensive array of modalities unavailable to writing: gesture, expression, pacing, register, silences, and clarifications—all of which are instantaneously responsive to listeners’ verbal and nonverbal feedback.”

-Dylan B. Dryer, “1.6 Writing Is Not Natural,” p. 29, in Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies

Earlier today, sitting at the bar of a bookstore/coffeeshop with our big winter coats slung over the backs of our chairs, my advisor and I talked about how all the scholarship I do and want to do starts with being in the same place with people. The same room. Talking about who we are, and where we are, and what we want.

“But why?” my advisor pushed. I struggled to answer. That’s why she was pushing: not because she doesn’t believe me, but because she wants to help me say the (messy) perspectives and commitments that weave through that experience.

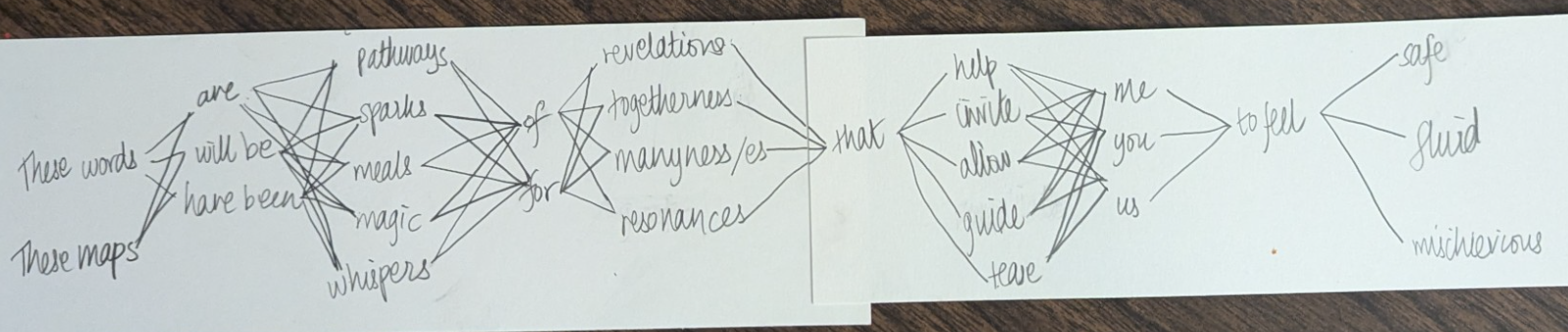

We talked for a long time, and I didn’t have an answer. I don’t have one here, either. But I like to think about Dryer’s point this way: talking with someone involves maneuvering through endless branching paths of opportunity. If we’re going to talk about my garden, we could start with the green leaves I glimpsed today, peeking out from the covering of my makeshift plastic sheeting and alive (I think!) through all of Illinois’ hard freezes. Or we could start by talking about your garden, whatever you’ve planted recently, and what other creatures came by to eat some of the raspberries last season, and how you feel about that, and how it changes your relationship to the squirrels, watching them bounding through your planted rows. Or we could start—so many places! And if we talked, in person, we’d find our path of possibility as a kind of mutual rambling, responding to each other in real time, maybe sharing some tea as we shared words. But in writing a writer is often positioned to make all these communicative choices before the you of who I’m talking to even starts out on this ramble I’m hoping we’ll share. Which points to another stark, and for me awful, difference. In talking about gardens we might both have a lot to say, but in the construction of writing there are these two strange roles. Writer. Reader. One “speaks,” one “listens,” it’s harder to play back and forth into the happy camaraderie of conversation.

So I was wrong. I do have an answer, or at least a rambling example about gardens. And all this is why I want my scholarship to start in conversation, not in writing. Why I’m more and more interested in writing primarily as a tool for opening and tending spaces in which we’ll come together to talk.