One of the (many) wonderful things about my friend Ishita Dharap is that I’m not sure how to describe our friendship.

We’re art friends. That can be drawing or crafting or eye makeup, familiar mediums, but it also means painting words into classes, balancing relationships into museum art exhibits, playing sunlight like you’d play a piano until it sounds sweet. Or maybe being a piano for some sunlight’s silly hands.

We’re cooking friends. That means we like sharing meals, love standing over the stove and stirring things, love the blur of heat and flavor into time and texture. I think it also means that we’re mischievously aware of ourselves as cooking, too. The idea for this post has been bubbling away on low for years. We make space for one another’s boiling and slow-bubbling.

We’re quick friends, ever since our first conversation while trees danced outside. Vibes, Ishita says.

We’re slow friends. Sometimes we don’t talk for a long time. That’s not a turning away or forgetting. It’s a growing— leaves that flicker in their curiosities, and roots that steady in their quiet, hidden curiosities.

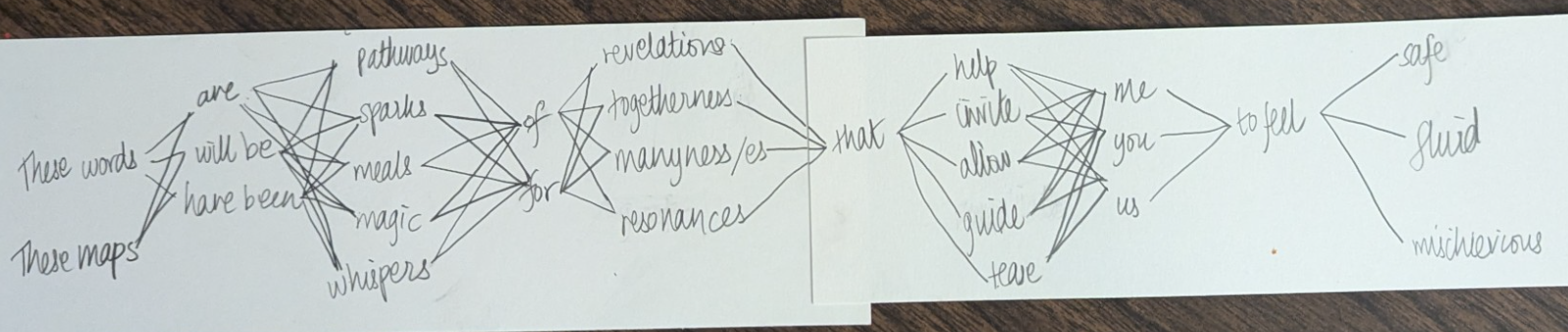

Did any of that make sense? Do you have friendships like that? Or maybe I should say like all these. I’m thinking about manyness. About how in my experience a friendship that is is many things. Ishita’s approach for mapping words into webs is one of my favorite ways to try and write that manyness. You can read in branching threads, following the different connections. People sometimes comment a lot about the linear structure of an English sentence, the sequence of a word then a word, but when I think about anything I’ve read the words are more a web than a line. Are they that for you? A knotted association of the threads above and this thread here and the next threads, and other memories or thoughts that all these threads tie to? They are for me, and Ishita’s word maps are a way of writing toward that web.